Dreaming Big: Australia’s first Ocean Plastic Supply Chain

Before WAW became a household name in the Australian surf industry, Rikki Gilbey was just another person dreaming big. What was driving him? Giving a new generation of bodysurfers a way to get barreled, while leaving nothing but a cleaner ocean in their wake. This is the origin of The BadFish – the world’s first, commercially produced, zero virgin plastic handplane. Bringing this dream to life is a story of failing fast which offers the rest of us eco-entrepreneurs inspiration in a world quick to label our innovations as “impossible”.

Figure 1: WAW’s BadFish handplanes are made of alternative materials. This gives the plastic waste a second life as a instead of ending in a landfill. Images courtesy of WAW.

Finding Partners with Purpose

Rolling out an ocean plastic handplane was supposed to take three months, instead it took three years. With a sigh Gilbey shares, “I was a bit naive going into the project, but the more I learned about the plastic problem the more determined I was to do something about it.” The puzzle pieces included an ocean plastic supplier, a molder, and a manufacturer – how hard could it be?

“Impossible” is a word Gilbey regularly confronted when pitching his idea in the quest for partners. Manufacturers in particular kept pointing to the risk ocean plastic materials posed to their expensive machinery. The issue, they argued, is that for ocean plastic to be recyclable and see a second life, extra time is required to separate the plastic polymers from contaminants (e.g., sand, shells, metal, etc.) The bottom line, sustainability’s arch nemesis, seemed to have won.

Plasticity, an annual forum to create a circular economy for plastic, gave Gilbey a fresh opportunity. Gilbey met an ocean plastic supplier, Louise Hardman, founder of Plastic Collective, and a forward-thinking recycled plastics manufacturer, Mark Yates, founder of Replas. Gilbey cornered both forum speakers with the same passionate message, “I want to prove that we can make something out of Australian ocean plastics, thereby giving others no excuse to make things out of the easier, cheaper and more readily available, post-consumer recycled material.” Aligned with Gilbey’s vision, Plastic Collective and Replas agreed to partner with WAW.

The partnerships took an investment of time, money and enthusiasm. Mark Yates and Gilbey ran experiments with ocean plastic material. Yates’ injection molding and recycled plastics expertise were key to getting The BadFish handplane off-the-ground and onto various retailers.

Through Plastic Collective’s Closed Loop Network, Gilbey teamed up with Ecobarge Clean Seas. Ecobarge Clean Seas had recently installed Plastic Collective’s Shruder machine, which processes the ocean plastic its volunteers collect into shredded recycled material. While other sources of ocean plastic procurement were too degraded and low in quantity for WAW Handplanes to rely on, Ecobarge Clean Seas’ source offered quality. The best part? The ocean plastic gets directly collected from the Great Barrier Reef. This means The BadFish’s entire global supply chain is local to Australia and offers lower carbon emissions than its competitors.

Figure 2: The Badfish handplane’s plastics supply chain. Image is courtesy of WAW.

What Makes WAW’s BadFish Unique?

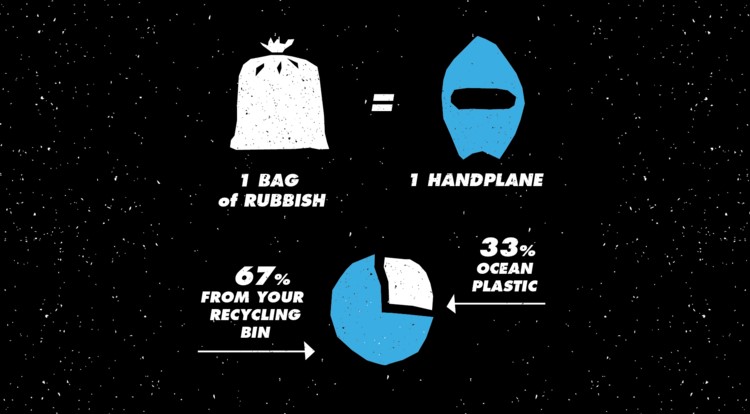

From there, success took off quickly. After three years of learning, searching and trialing, The BadFish became the first, commercially produced, Australian made product utilising a traceable Australian ocean plastics supply chain. In fact, each WAW BadFish gives one bag of rubbish (a.k.a recovered resources) a new life. This 99.9% recycled product is made with ⅓ recycled ocean plastic and ⅔ kerbside recycled plastic – mainly milk bottles, packaging materials and items like single-use plastic like cutlery, fishing equipment and plastic bags. The other 0.1% is a UV stabilizer that prevents further breakdown to protect Oceans from micro plastics.

Figure 3: Recycled plastic ratios in WAW’s BadFish. The Badfish is taking tons of plastic out of the ocean every year and driving environmental impact. Image is courtesy of WAW.

A unique aspect of WAW’s sustainable products is that they never asked consumers to make a sacrifice. The BadFish offers an equal bodysurfing high, a product with a purpose, and (drum roll please!) a handplane that is 10%-36% below competitor pricing. WAW proves, like a growing number of innovators, that sustainability does NOT require compromise.

Nowadays, numerous Australian bodysurfing clubs back WAW and bodysurfers, like Australia’s Corey Sainsbury and World Bodysurfing Champion Tom Marr, all sport WAW BadFish gear. Mission accomplished? Not quite yet.

Scaling & Sourcing: Lessons from Australian Waters

WAW is facing a new challenge. As of 2021, consumer demand now outpaces its supply of recycled ocean plastic. While Ecobarge Clean Seas’ collection levels are high, its reliance on volunteers for the cleaning process is a bottleneck. This supply chain disruption is creating a scalability issue.

WAW is now working with Plastic Collective’s Closed Loop Network to find a partner to bridge this gap. The goal is to bale collected ocean plastic and, with the help of a new partner, process the material into recycled ocean plastic feedstock for WAW’s use. Gilbey also plans to make this processed ocean material available to others, in the hope that more businesses will incorporate it into their products.

On the Horizon: Inspiration to be the Change

Gilbey will continue developing new ocean plastic products in the future. His driving force is to prove, time and again, that using ocean plastic is not only possible, but profitable. If more companies use ocean plastic, the heightened demand will lower costs and make the material competitive to virgin plastic. (The main excuse industry points to.)

Gilbey is also quick to say, “Why go and buy brand new material when the resources are right there ready to collect and everyone is just paying to throw it away?” To get this message out, WAW is being:

- Persistently genuine: From the very start, WAW wanted to properly create an ocean plastic product. This meant taking a real step to solve the ocean plastic problem locally, not stopping at marketing. WAW has remained genuine to this mission and Gilbey regularly reminds himself not to give up as it’s hard, not impossible.

- Transparent: WAW isn’t afraid to tell it as it is. Challenges like ocean plastic are complex. If it were easy, it would not be on the global agenda. WAW believes it has an obligation to share the good, the bad and the ugly of their journey with others. Much of this can be found on its website here and here. The Badfish can be added to a growing number of case studies.

- Loud: Gilbey, who prefers bodysurfing to public speaking, is a big believer in inspiring others to take action. He takes every opportunity to share WAW’s journey to make it easier for others to join.

This unfolding adventure may sound like a serious amount of work, but Gilbey and the WAW team leave plenty of time to get barreled while leaving nothing but a cleaner ocean in their wake.

Figure 4: The Badfish handplane in action! Images courtesy of WAW’s Instagram.