“Lets start talking about people again, lets talk about exploitation”.

– Chris Evans, Australian Anti-slavery Commissioner (UNBHR, 2025).

Over 300 people from multiple business, research and civil sectors came together for the UN Business and Human Rights Regional Forum in Melbourne, hosted by UN Global Impact Network Australia. The 2-day conference focused on various Australian and New Zealand companies’, and their operations which may adversely impact people, communities and environment causing exploitation and human rights abuses.

This focus on people and exploitation is also central to Plastic Collective’s mission. For us, tackling plastic pollution must always go hand in hand with protecting dignity, fairness and community wellbeing, while helping businesses embed due diligence and social safeguards into their operations.

The first event launched at the conference was Oxfam ‘s report called ‘What she makes is keeping her in poverty’. Oxfam’s team has documented how the Australian fashion industry is benefiting from increased profits which are being made from predominately women garment makers living in impoverished countries including India, Bangladesh and China.

The income these women receive is often below the living wage, keeping them in a cycle of poverty, while the fashion industry in Australia and New Zealand is booming. Oxfam recommends that Australian Human Rights laws need to be amended to make businesses more accountable for human rights abuses within companies supply chains.

The conference included a diverse array of companies, legal consultants, affected community leaders and other stakeholders. There were robust and honest discussions about the current laws which businesses are required to adhere to (or lack of suitable laws), which aims to prevent abuses within communities where Australian and New Zealand companies operate.

There was an overall consensus from the business leaders to avoid and prevent harm from being done to communities (people and environments) from their operations, as well as a unanimous desire for the government to implement stronger laws in both Australia and New Zealand. These laws should provide communities and businesses with the legislation and tools to prevent human rights abuses through transparent engagement, due diligence, just transitions, mandatory reporting and penalties for breaches of human rights.

Legislating mandatory reporting of companies working in high risk areas was a key theme throughout the conference, as well as ensuring all businesses apply due diligence within the supply chain to avoid human rights abuses, particularly in lower socio-economic countries who are engaged to provide goods and services, including Bangladesh, India and China. Extractive mining in Pacific Island nations was also a key area which needed stricter regulations and monitoring.

Multinationals Impacting People & Environments

The conference also heard from communities in PNG, Fiji, Palau and other Pacific Island states where large Australian multinational companies – particularly mining, fishing and forestry companies, have been operating without suitably connecting to and respecting the local indigenous people or their land. A lack of meaningful engagement and unregulated exploitation has led to social and environmental abuses impacting multiple downstream communities.

Community leaders from Fiji Council of Social Services also presented their experience with Australian company Amex Resources Ltd which started dredging the Ba River in 2019 for magnetite (the first Black Sand mining in Fiji). This company lacked due diligence and full community engagement, which is now causing serious harm to the local communities and the coastal environment they depend on.

Amex Resources’ overview statement is ‘by its very nature, mineral exploration can disrupt natural ecosystems and local economies and trigger effects in communities’. The lack of relevant ESG policies to prevent damage being done to local indigenous people and their environment is causing harm in Fiji. Law firm Jubilee Australia is currently working with the indigenous communities to address this.

Lessons should be learnt from the long-running example of Rio Tinto’s gold and copper mine in Bouganvillea PNG, where extreme environmental destruction occurred between 1972-1989 when Rio Tinto discarded a billion tonnes of mining waste into the local rivers. This led to a civil war in 1989, which resulted in over 20,000 people being killed. No cleanup ever took place and retribution for damage done.

In 2020, 170 Indigenous Bouganvillean people and the Human Rights Law Centre filed a complaint to the Australian OECD National Contact Point for Responsible Business Conduct (AusNCP). British-Australian owned Rio Tinto finally agreed in 2021 (over 30 years later) to fund an independent impact assessment. Released in 2024, the Panguna Mine Assessment has now led to funding solutions to address the severe and ongoing disaster in Bouganvillea.

As a global business working closely with communities impacted by plastic pollution, Plastic Collective was very interested to hear about the different ‘tools’ available for communities and individuals to report unethical and harmful operations being carried out by multinational companies overseas.

In addition to supporting communities, Plastic Collective is also keen to support companies and businesses to do the right thing, ensuring they conduct their due diligence and proper ethical engagement by listening to communities, particularly on Indigenous peoples lands.

Two especially useful tools highlighted at the Conference were the National Contact Point (or ‘NCP’) for communities to redress damage done to their people and environment, and Fair – Prior – Informed – Consent (or ‘FPIC’) tool for companies to prevent future damage by engaging with individual and collective rights of indigenous people.

NCP’s – A Redress Tool For Communities

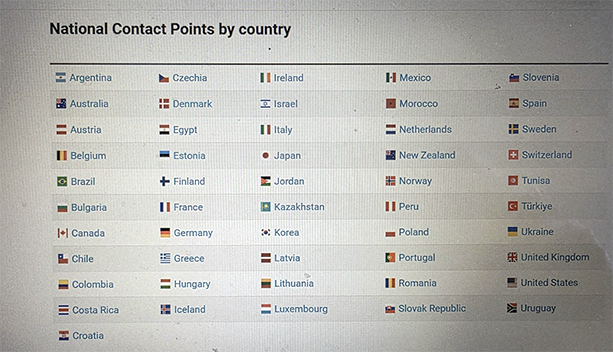

When companies negatively impact local people and their environment by infringing on human rights or causing environmental degradation, there is an avenue for addressing the problem – National Contact Points (NCP’s) available in 52 countries.

The origin of NCP’s comes from the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operations & Development) which was established in 1961 with 38 democratic countries, The OECD Vision for the next decade is summarized as;

“The world faces significant and growing challenges that require global cooperation and action. We, the Members and the EU reassert our core values and reaffirm our founding goals. Together we work towards strong, sustainable, green, inclusive and resilient growth and renew our commitment to the sustainable development of the world economy with a transparent, accountable and inclusive Organisation.”

OECD Responsible Business Conduct standards enabled guidelines for Multinational Enterprises Conduct to be developed including the establishment of 52 National Contact Points (NCP’s) throughout the member countries, including Australia (AusNCP) 2020 and New Zealand (NZNCP) 2002.

The NCP complaints are reviewed by independent examiners to resolve major issues, as in the case of Rio Tinto which led to a landmark multimillion dollar redress scheme. NCP also provides a platform for companies, NGOs and institutions to raise awareness of responsible business conduct through additional resources.

You can read more about the complaint process on their as well as Guidelines for Responsible Business Conduct. The NPC’s database of cases covers the member countries with peer reviews and is an open source for people to check if multinational businesses are acting ethically.

FPIC (Free , Prior, Informed, Consent) ENGAGEMENT – Tools for Companies

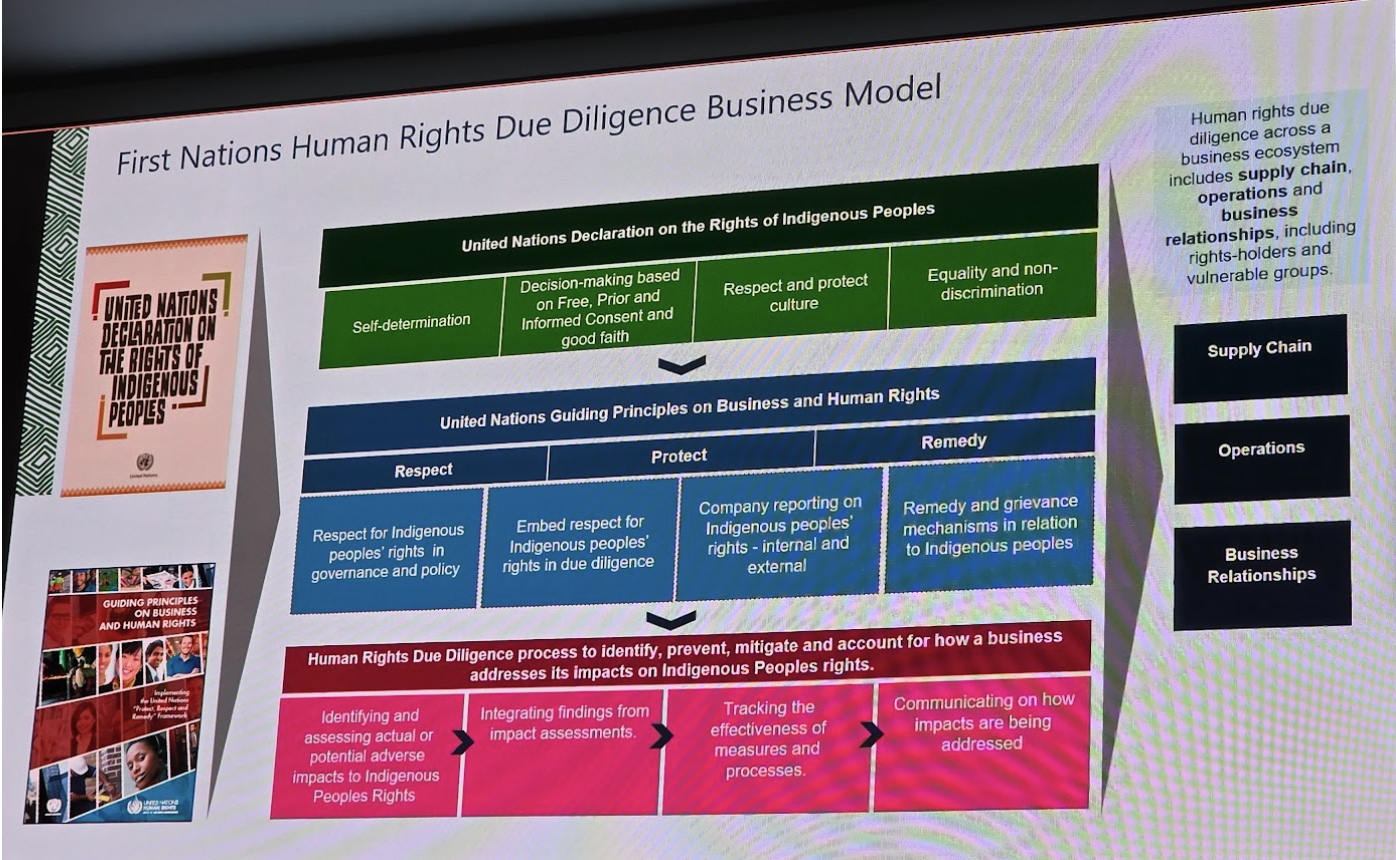

‘FPIC’ was established as a way for companies to engage and develop a meaningful collaborative partnership with First Nation and Indigenous communities. Developed by the indigenous communities themselves and supported by the international and civil communities, FPIC was formulated through the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Convention No. 169 (1989) and later embedded into the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007 (UNDRIP).

The Australian Human Rights Commission enacted UNDRIP in 2009, which has 4 pillars of Indigenous Rights – self-determination, participation in decision-making, respect for and protection of culture, and equality and non-discrimination.

As many projects including mineral extraction are located on Indigenous lands, companies must have a policy to engage with, and develop consent (or no consent) for project approval. This involves conducting human rights due diligence in alignment with indigenous rights.

The Free-Prior-Informed-Consent (FPIC) method of engagement ensures indigenous people lead the consultation process and participants follow four key components;

- Free: The process should be directed by the community being engaged, they should be free to consent (or not to consent) without coercion, intimidation, manipulation or forced timelines. The process should be self-directed by the community from whom consent is being sought.

- Prior: consent is sought sufficiently before any authorisation or starting of any activities.

- Informed: information provided to the community should be clear, consistent, accurate, constant and transparent. The community should choose the appropriate language and culturally appropriate format and engagement for the sharing of the information.

- Consent:refers to the collective decision made by the rights-holders and reached through the customary decision-making processes of the communities.

Indigenous and First Nations peoples have strong community and cultural ties, making their desire to enhance the social, environmental and economic outcomes for their people a vital component when engaging with external entities. Respectful engagement leads to strong and lasting relationships for businesses with good ethical and ESG policies. FPIC is a key tool used by Plastic Collective in its project certification process under the Verra Plastic Waste Reduction and Zero Plastic Oceans Social Plus Standards.

Corporate Due Diligence & Living Wages

Under the ICJ (International Criminal Justice), States and Businesses have an obligation to ensure impacts from climate change and human rights are prevented through due diligence. The vast majority of companies and businesses want to do the right thing, by engaging in meaningful dialogue with communities and local people, following due diligence, and being transparent and accountable for their operations in other countries. However, when working across many regions, it can also be difficult to navigate different rules in different countries.

Companies are guided by increasing profits for their shareholders. As wages for workers in different countries vary greatly, this leads businesses choosing to set up operations where labour is cheap and profits can be increased. However, do they adhere to minimal wages or living wages?

‘Minimal wage’ is legal income set by the government in each country an employer must pay an employee, while the ‘living wage’ is an income level sufficient to maintain a decent standard of living for them and their family covering basic needs like food, housing, healthcare, childcare, and transport.

Differences between living wage and minimum wage can be high in some places. WageIndicator Foundation provides a database for 178 countries across 3000 regions for companies to check the disparity between wages. Understanding how a living wage can prevent ongoing poverty and unethical human labour conditions, can prevent companies from unknowingly contributing to human rights abuse.

For Plastic Collective, this issue is especially urgent in the context of waste pickers, who are the often overlooked workforce responsible for collecting more than 60% of the world’s waste. We are actively championing the Living Wage Goal, an initiative designed to materially improve waste picker livelihoods and embed fairness into the global plastic value chain.

Our research in Ghana, Indonesia and the Philippines shows that waste picker incomes often fall below even the minimum wage, let alone a living wage benchmark. By advocating for the Living Wage Goal as part of a Just Transition under the UN Plastic Treaty, we are working to ensure that waste pickers are paid fairly, provided with healthcare, and supported through social protections.

While this goal is still in development, momentum is building through mechanisms like the Social+ Standard and the Plastic Waste Reduction Linked Bond. Together, these efforts are moving the business community closer to a future where living wages become a reality rather than an aspiration.

Business Needs Strong Government Policies

The big issue for the Australian government is the lack of penalties for companies who infringe on human rights, as well as a lack of mandatory due diligence reporting, plus high risk declarations not being compulsory.

Speakers in the conference talked about how many representatives in the Australian parliament lack understanding of high risk declarations and how business can adversely impact on human rights globally. With 400-1000 companies in Australia not reporting on high risk overseas operations, it is imperative that human rights literacy is improved through sharing knowledge and a focus on people.

We also heard about how New Zealand’s conservative government is currently trying to wind back established laws around Indigenous (Maori peoples) rights and other measures. NZ is currently waiting for the government to introduce the Modern Slavery Act, which Australia had introduced in 2017.

All participants at the conference agreed that Human rights and First Nation rights should be embedded throughout a companies’ policies for negotiations, setting up supply chains and ongoing ethical relationships. Modern slavery and forced labour should be abolished, the living wage should be part of a company’s due diligence and ESG policies, particularly in countries providing goods and services to us all and on other peoples lands.

The business community can do a lot when it comes to lobbying their governments to respect people and their environment through educating our politicians to implement strong human rights laws, mandatory due diligence and reporting, as well as penalties for human rights abuses.

And while governments must step up, businesses don’t have to wait. At Plastic Collective, we’re here to help the business community go beyond compliance and maximise its positive environmental and social impact, from tackling plastic pollution to strengthening human rights across supply chains. This can be achieved not only through the frameworks discussed here, but also through new opportunities we are building with partners worldwide.